Blog

Why is it so hard to do nice things, that make a difference, with other people?

Our presentation from Electromagnetic Field Festival 2022

This article is a bloggified version of the talk I gave at EMF 2022 aimed at a hacker/maker/creator community. It’s a bit rougher and more personal than our usual posts, so I hope you like it, and I would love to talk to you all about it over the following months.

Part 1: on the desire to do stuff

I started Geeks for Social Change in about 2016, first as a meetup group, then a reading group, then a research and design studio, and now a collective and studio combo (more on this soon). This came out of a desire to blend together activism, tech and research in groups I was in to make things better and create truly community-led tech. I’m basically a scrappy activist deeply embedded in feminist, trans, abolitionist, antiracist politics, who couldn’t see myself represented anywhere in tech, and the rising term ’tech for good’ hitting extremely wide of the mark for what community groups I worked with needed. I’m now just about ready to start getting all these feelings out my head and onto the page.

Like a lot of long term activists, I was also very burnt out from activism and wanted to do something joyful and fun, to be able to deliver projects with a very “fully automated luxury queer communism” vibe. To get away from the coalface a lot of activism can find itself stuck at, and make a place to actually start building the world we want to live in rather than just fighting the old one.

Making as a basis for joy

I like to think almost everyone has some form of making, coding, producing, sewing, sculpting, knitting, instrument playing, or other arts and crafts process, as a coping mechanism. An activity that’s just for you that brings you joy for its own sake.

It feels like we can’t change a lot in the world at the moment and things are pretty grim, but we can at least make some cool doodads. The process of making (or producing) can be therapeutic, keeps us mindful, lets us use our hands, work in non-hierarchical ways, and generally fuck around and find out with low stakes.

I think this is potentially a really really deep form of interacting with the world and at the core of what gives our life meaning. However, we are not really living in a society that allows this joy to be at the forefront of our lives, making it something we have to fit into the cracks.

“We live in a world which is generally disagreeable, where not only people but the established powers have a stake in transmitting sad affects to us. Sadness, sad affects, are all those which reduce our power to act. The established powers need our sadness to make us slaves. The tyrant, the priest, the captors of souls need to persuade us that life is hard and a burden. The powers that be need to repress us no less than to make us anxious … to administer and organize our intimate little fears.”

(Deleuze, 1988)1

Deleuze talks here about “the power to act” as the basis of our entire being. Whether we want the power to eat a burger, play with our phones, design a shader on stage, build something out of scaffolding, turn some mercury into gold, or whatever else people did at EMF Camp, we are fundamentally empowered or limited by our collective and personal power to act.

Doing stuff as an escape from the drudgery

I think the effort that is currently needed to begin and maintain these things that bring us joy is really something that needs attention. Especially given many people have jobs they hate and they do stuff in the evenings or weekend to feel valued. David Graeber for example points out that the more you get paid, the less likely your job is to improve society2. Our ease of being able to do these things that bring us joy drastically affects both our perception of the world and feeling of control over it.

Making is for many our escape from oppressive power structures. Almost every talk in the EMF program is not someone’s day job, or if it is they’ve had to jump through burning hoops to make it their day job. This is what we do for fun. Isn’t it mad that these niche interests, the things that bring us joy, and that bring a field of people together, are pushed so far from the margins that we can’t even imaging this being the main thing we do? We have a potential wellspring of new ideas and the people who want to make a better world, and yet that space is pushed right to the margins.

at night showing lit up pathways, big tends, and a glowing purple tent.](/blog/2022/why-is-it-so-hard-to-do-nice-things/emfcamp_hub5c7ea2de48807e7fbed3c32aea4c8fb_118932_900x0_resize_q75_h2_box_2.webp)

The joy I’m talking about here isn’t the joy you get from going to a party or taking drugs, say. I’m talking about the satisfaction of setting your mind to a hard problem and fixing it. This is about the stuff that gives life meaning and makes you feel alive, gives you agency over months and years, not days and weeks. Doing good projects that matter and accomplishing things you thought previously impossible can be one of the most rewarding things there is. Anyone whose been part of putting on a big event or producing some collective artwork generally has a huge sense of pride about it. These are the things that form part if our identities, and change who we are, how we think, and what we think possible.

So in summary: doing and making stuff not just fun but possibly a basic form of interacting with the rest of the universe. Capitalism is bad, and gets in the way of this. If you think this sounds like communism or anarchism, yes you’re probably right.

Part 2: on the difficulties doing the stuff with other people

A completely reasonable desire given the joy of doing things is then to want to do things with other people. And this is where it gets messy, because people are messy and relationships are hard.

This might be setting up a hack space, forming a D&D group or knitting circle, going LARPing, making a Minecraft server, or just organising a weekly meetup at the pub. We could call this ‘apolitical’ organising (although obviously everything is political!).

It could also be trying to mobilise some friends to go to a protest, form a mutual aid group or trans clothes swap, put on a zine fair, or organise a vaguely political film festival or club night for a minoritised group. We could call this ‘political’ organising. As you can see there’s really no clear distinction between the two but let’s go with it for now.

While the core of the activities is very different, the actual activity becomes the same: building relationships and organising communities. Again, these relationships are usually the ones that give our lives meaning -— doing fun things things with like with people we love is the one of the best feelings on earth. In other words: the work becomes more about relationships and less about the original activity we started with.

We’re not really taught how to work cooperatively at any point in our educational or work systems. Despite the fact it’s more or less the default way of working between friends and hobby groups, we don’t really learn about different ways of doing consensus or consent, conflict resolution, restorative justice, or a bunch of other stuff that would really help. So it can be tricky because we’re just short of tools and experience and we’re short of other people to help fix things when stuff goes wrong. So just as it can be great organising things, it can also suck. A lot.

It is this relationship work that is the thing the rest of this piece will really focus on.

Communities of Place and Interest

We all exist within communities of place, and communities of interest. These both deserve a bit of attention and thought as to how they differ.

Communities of place are, basically, where we live. This is our immediate neighbourhood, the things we walk past every day. This used to be the main space for what we would consider “community life” but now to many can feel really alienating. I live in a very mixed inner city area (Hulme in Manchester) and see up close how age determines where and how far people will travel — the student population keeps itself to itself (not half because of the gigantic fences erected by the university) and socialises in the city centre while older people, especially minoritised ethnic groups, end up living near each other in ways that are invisible to outsiders.

This is self-selecting in itself — postcode at birth is still the single biggest predictor of your life chances and choices — but in the rarefied world we live in it feels like this can be the closest thing we have to meeting people outside our self-selecting hobby and identity groups.

Communities of Interest are what they sound like. The stuff I talked about in the first section of this paper. The rise of the internet has made these far far easier to do (and sort of shoved out the ones of place for those who are really online). The locus of attention is the interest or hobby itself, and creates its own habitus that transcends any one place.

The interplay between the two can be hard, and is why I think it feels so hard to do stuff right now. We are sort of in a new era where such a large proportion of the population is a bit too online, in ways that are entirely controlled by gigantic oppressive companies, who directly set what behaviours are possible and impossible. This has both increased alienation between the on and offliners, as communities of place all of a sudden seem really difficult to engage with. Safer to stay talking to my friends where its safe.

On some level we are all working in a crossover of the two. The size of the geography expands as the size of our interest gets more niche. So for example it doesn’t make any sense for me to think about trans organising in my ward, there’s just not enough people (ok, where I live specifically there might be but in general not). As a group that is 0.3-0.5% of the population we need to cast a net over wider areas. But if I’m thinking about protecting local parks or meeting neighbours for coffee I’m thinking you know, 200m from my house. And I’m also expecting people outside that radius to not really care where I go for coffee or to a park because they have their own. But these interest-based groups silo fast, and then get more and more niche, and eventually scene drama somehow becomes your life.

And then let’s just not leave it unsaid…

Doing stuff right now, under a Tory government

I hope it is not controversial to say: politics in the UK (and world) fucking sucks right now.

We live in extremely disempowering times. It feels like it’s hard to talk about possibility and change right now as we spend so long struggling to exist: the intersecting cost of living crisis, ongoing pandemic, corrupt and fascist government, social isolation and loneliness crisis, upswing in structural racism and hate crime, and highly coordinated and well funded attacks on trans people are creating an incredibly intolerant environment. Covid has torn apart a lot of the normal functionings of how people go and find communities of place and hyperfocussed the ones of interest.

I think a lot of us, especially those who are perhaps two or more of trans, disabled, of colour, neurodivergent, working class, queer, carers, and other marginalised groups have never been further from representation at the ballot box. This is the rant part of the talk before I get talking about more constructive things. The Labour Party in waiting looks like Tory-lite, and on some issues is more right wing than the Tory party. The minority parties never look like serious contenders on any issues and don’t seem to have any real teeth outside of just “not that guy”, and the mainstream alternatives to that suck too. Join that up with the billionaire press in this country, and yeah. Not good. A lot of us simply not only see no representation of ourselves at all, we have almost daily attacks on our rights to exist everywhere we look.

To be clear I really respect people trying to make change in any of these big institutions. I’m just increasingly finding that this whole sorry mess is not something I care about any more, and most of the community organisers I work with locally feel the same. I think it’s time for us to go back to basics and figure out what community means again, as this is very often taken for granted.

Injecting big-P politics into our work unfolds in confusing and complex ways. Theres something inherently cringe feeling about doing any politics. I feel like everyone I talk to who does organising feels this in their soul. We do everything we can to avoid terms like ‘activist’ and spend an awful lot of time annoyed at other people. This talk made me cringe to write. But hey: I am cringe, but I am free.

People think of activism as protests or being obnoxious on Twitter, and for many that’s the front door, but we simply need to find better and more ways of being able to resist this sorry state of affairs that are inherently joyful, sustainable, inclusive, and can actually pay people a wage to do. Ways that centre the needs of structurally marginalised groups and take us back to what really matters about all this: enabling collective joy.

On the classed and gendered nature of free time

I was invited to talk at EMF under the ‘EDI’ (Equality, Diversity and Inclusion) banner, because some on the festival team realised it has a problem and wanted to make the festival better represent the UK’s wider population. There are a lot of structural reasons why this is the case – the idea of it being someone’s ‘fault’ is unhelpful here – but it’s important to be explicit about why this kind of initiative is important and what we hope to gain from investing in it.

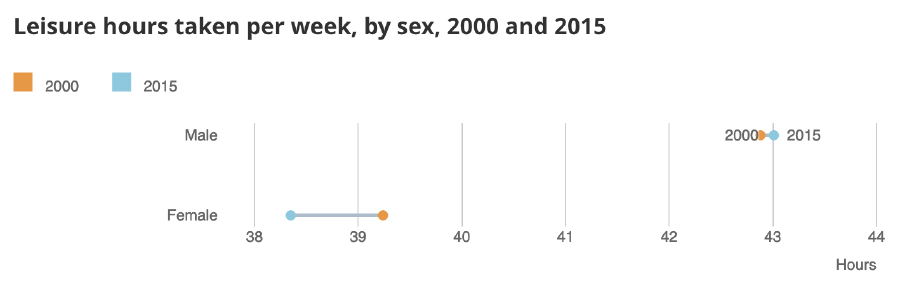

An ONS study3 showed that men have five hours more leisure time a week than women every week. That’s a whole hobby. So there’s a side of this “free” labour that is radically classed and gendered, and tied to disposable income and caring responsibilities. Leisure time is therefore something people have highly varying quantities of and is drastically classed, gendered and probably racialised, before we even decide what to do with it.

I think this dynamic by itself results in so much of what we see unfold in terms of hobby group makeup. And a lot of this is because of larger issues to do with the unequal distribution of care labour, unequal pay, etc. But it also ties into a disability activism narrative where if activities are uncritically based around the idea of the normal, normative, able bodied person, who Grayson Perry coined “Default Man”, we are just always going to be reproducing the harmful construct we’re placed within.

Jos Boys talks about this basic tension in a disability studies context:

Why does the idea of disability being creative and avant-garde seem so absurd? Is it because of the taken-for-granted assumptions about disabled people that they are in need of the help of others, are passive consumers of services, constitute a minority of individuals in society who (unfortunately) must bear the brunt of their own medical problems? […] What if, instead, we see that rethinking disability enables us to explore critically and creatively assumptions about […] disability and ability, which, in turn, can offer better ways of understanding the […] implications of both bodily diversity and everyday social-spatial practice? (Boys, 2014)4

Why is this so hard!!!???!!!!!

Anyone whose tried to organise anything can attest to how utterly thankless it is most of the time. I think especially for the political spaces, a bunch of the following are common experiences I’ve heard over and over that I paraphrase here:

- “I tried to help out with some activist stuff, but everyone was just too busy yelling at each other and I didn’t feel I could contribute”

- “People on the left are complete dicks and I got in shit for some stuff I don’t really understand and no-one bothered to explain to me”

- “I tried to help out at a community centre but they were just really disorganised and never get back to me”

From the other side, for groups needing help this can be just as frustrating:

- “People keep coming to us with what they want to do and not asking what we need. The real issues here are complex and layered and don’t have simple fixes or someone would have done them.”

- “We had a volunteer make a website but they didn’t really listen to us and no-one knows how to operate it. We’ve now got to make a new one without upsetting anyone.”

- “Volunteers keep coming and promising us the world and then vanishing. It makes it really hard to plan things and means we have to assume the worst a lot.”

There’s no easy fixes to any of this stuff. Because of the vast underfunding of this sector by the Tories, groups can have an awareness they’re putting people off but don’t feel they can make the time to find out why.

A lot of this though is simply because when you step outside normative contexts where people are in hierarchies and have similar social capital, you start dealing with actual breakdowns in society and that can be really jarring. Structural discrimination is very ugly, operates on multiple scales, and the dynamics have existed long before you were born and will continue long after. Putting your toe into it can feel like getting it bitten off. It takes a lot of hard work to do the work of decolonising yourself, unlearning racism, transphobia, classism, etc. In many ways it’s a life’s work. Especially for white middle class people like me, meeting people where they are that they have the power can feel initially incredibly disconcerting.

It is this we try and tackle head on in our work.

Part 3: on Community Technology Partnerships

In the last section I’m gonna talk about GFSC’s approach to navigating all this stuff, and how we sort of want to take apart how people think about tech and put it back together again in a way that overcomes these ideas from the ground up. Despite working on this idea since 2017 we’re still working through this and are very much at the start of our journey so please come talk to us about it. You can join our discord server if you like, or send us a tweet or email!

To recap…

On the surface of it it seems simple: tech and maker types have skills they enjoy using, and community groups have unmet needs that could be helped by these skills. Why then does it feel so incredibly hard to make these collaborations happen in reality?

What we increasingly found developing GFSC was that the methodologies we have to do good work are just not fit for purpose. Design Thinking and Human Centered Design are two such approaches that proclaim to be liberatory but actually just end up revolving around the idea that what we need is expert white middle class able bodied people on high salaries to come and helicopter in and fix things and then leave. This is the kind of “uber, but for…” model. Uber, but for poverty. Yeah, no.

The Capability Approach

My earlier journal paper with Prof Stefan White built heavily on one key existential question:

“What are the people of the group … actually able to do and be?

(Nussbaum, 1999)5

The Capability Approach is a human development methodology used by the UN and WHO for their sustainable development goals developed by Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen. This simple question asks what people are able to be and do, and asks how we can remove blockers to these concrete actions and states.

This seems like a simple question but is both a concrete ethical test that respects people’s fundamental existence, rather than having choices ‘made for them’ on the basis of external characterisation or assumptions of their abilities, feelings or opinions. By basing our work on this human development approach, rather than something from within product design or the tech industry, we think we’ve found a way to reconfigure this fundamental relationship in a wider (i.e. non technical and pre-existing) moral framework.

Community Technology Partnerships

In other words, people are the best judges of their own personal circumstances and neighbourhood. They therefore are the best placed to fix it. Our approach to codifying this has three stages:

- direct engagement with and involvement of,

- multiple stakeholders in a place-based creative partnership,

- actively enabling realisation of self-defined opportunities for individuals and groups.

(White & Foale, 20205)

Essentially this means:

- Talking directly with and engaging a range of people,

- Getting them around a table6 in your neighbourhood in a way that allows decisions to be made collaboratively,

- And in doing so enable everyone to achieve new things that they want both individually and as a group

The explicit goal of this approach is therefore to increase collective power to act, to increase the things we can do or be. Have you ever felt like it’s not possible to get stuff done? And then moved to another city or a maker camp like this, or fell in with the right group of people, and suddenly you feel like you can do any number of things? This is what we’re getting at. How do we make places feel full of potential, creativity and joy? Beginning with inclusion and collaboration as a central principle creates the conditions for this.

This is enough for one blog but a few examples from our work we will go into another article:

- With imok, we worked with No Borders Manchester to make a tool that replicated their existing process,

- Taphouse TV Dinners was a collaboration between multiple groups working in Hulme and Greenheys to provide free food for vulnerable residents,

- PlaceCal is our flagship tool that has set up a new nonprofit partnership of local community groups who want to work together to publish information about events and services

None of these interventions really resemble an ‘app’, or what people think of when they talk about tech. They’re all complex mixes of community development work, some software either old or new, and a commitment to training and education. This work is really hard to talk about at the moment in much more detail than that because we’re trying to create a basis for emergent systems, not deterministic ones, and we are barely off the starting blocks working on it.

I’ll end on a quote:

“the space beyond fixed and established orders, structures, and morals is not one of disorder: it is the space of emergent orders, values, and forms of life”

(bergman & Montgomery, 2017)7

How can we disrupt the monopolisation of the internet by the big five tech companies and create our own structures based on mutual support, joy, inclusion and accessibility, that allow us to centre our basic desire as humans to create things?

I have no idea but ask us in a year.

Talk to us!!

Let us know if you want to get involved in this kind of work. We’re just starting some big exciting projects and would love to have you with us.

- You can chat to us on the GFSC discord

- Follow us @gfscstudio on Twitter and Instagram

- Email me: [email protected]

Thanks to Dr Colleen Morgan for her utterly invaluable input into this piece.

-

Deleuze, Gilles (1988). Spinoza: Practical Philosophy. City Lights Books, San Francisco. Download ↩︎

-

Graeber, David (2018). Bullshit Jobs. Simon & Schuster. ↩︎

-

Office for National Statistics (2018). Men enjoy five hours more leisure time per week than women: Men in the UK enjoy nearly five more hours of leisure time per week than women, ONS analysis reveals. Retrieved online. ↩︎

-

Boys, Jos (2014). Doing Disability Differently: An Alternative Handbook on Architecture, Dis/ability and Designing for Everyday Life. Routledge, Oxon. ↩︎

-

Cited in: White & Foale (2020). Making a place for technology in communities: PlaceCal and the capabilities approach. Information, Communication & Society. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Or virtual equivalent, but the point is it’s people you live close enough to to physically visit and create relationships with that are not solely around shared interests. ↩︎

-

bergman & Montgomery (2017). Joyful Militancy: Building Thriving Resistance in Toxic Times. AK Press (link). ↩︎