Blog

Why tech co-production practice is barely scratching the surface

Revisiting Arnstein's "Ladder of Citizen Participation"

There’s a lot of discussion about co-production, co-design and other impressive-sounding terms starting with ‘co-’ at the moment in tech1 circles. These terms long predate tech and generally have their roots in urban planning and civic policy. Despite all the hip methodologies such as ‘service mapping’ and ‘human centred design’, many in tech seem to miss the original point of these methodologies: to give complete power to the community that work is being done ‘on behalf’ of. In other words, there’s nothing special about any design methodology. Change happens when the balance of power is shifted, otherwise it’s just potentially well done and engaged market research.

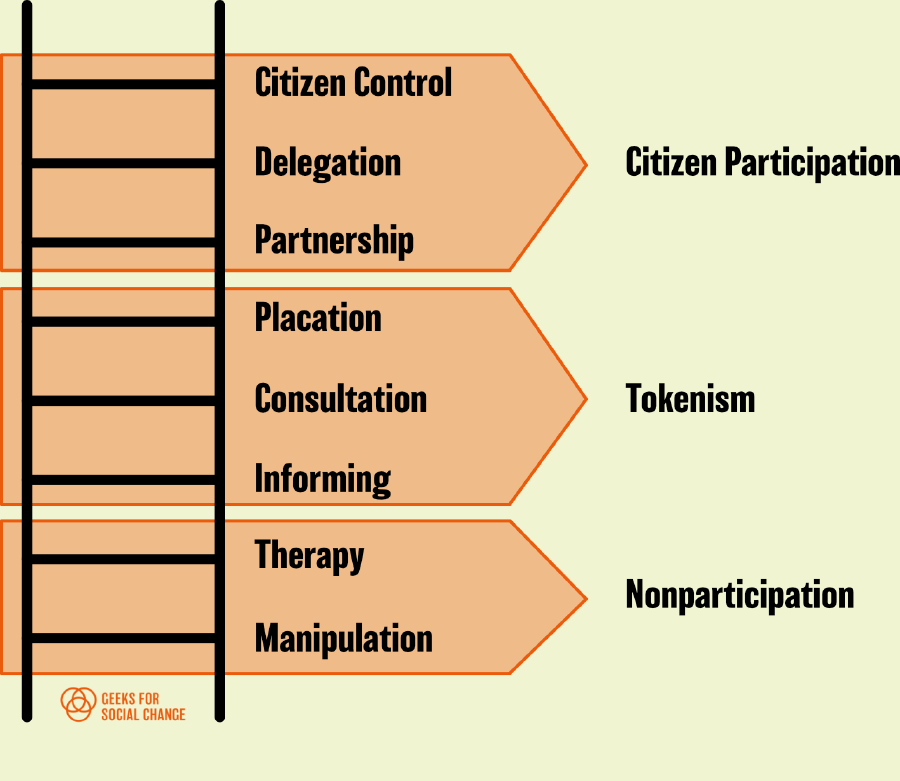

I realise a lot of this knowledge hasn’t made it into mainstream tech discourse yet, so I gave an overview of Sherry Arnstein’s classic 19692 piece “A Ladder of Citizen Participation” at a Tech for Good Live event last week. I think that tech has a lot to learn from other areas of civic coproduction, especially as it’s now more than 50 years old! Some of the language now seems outdated, and there have been countless riffs on it (19018 refs on Google Scholar at the time of writing), but the core concepts remain the same. Here’s the ladder, redrawn a little by me. This article will relate the ladder to some practices I see in community engagement and tech practice today.

Nonparticipation

The bottom two rungs of this are categorised as ’nonparticipation’. ‘Manipulation’ is a very common first step when organisations want to be seen to involve communities, in which “people are placed on rubberstamp advisory committees or advisory boards for the express purpose of ’educating’ them or engineering their support”. ‘Therapy’ is a little harder to describe, and I’m not sure translates as well to today:

“In some respects group therapy, masked as citizen participation, should be on the lowest rung of the ladder because it is both dishonest and arrogant […] people are brought together to help them ‘adjust their values and attitudes to those of the larger society’”, diverting them from the real issues …

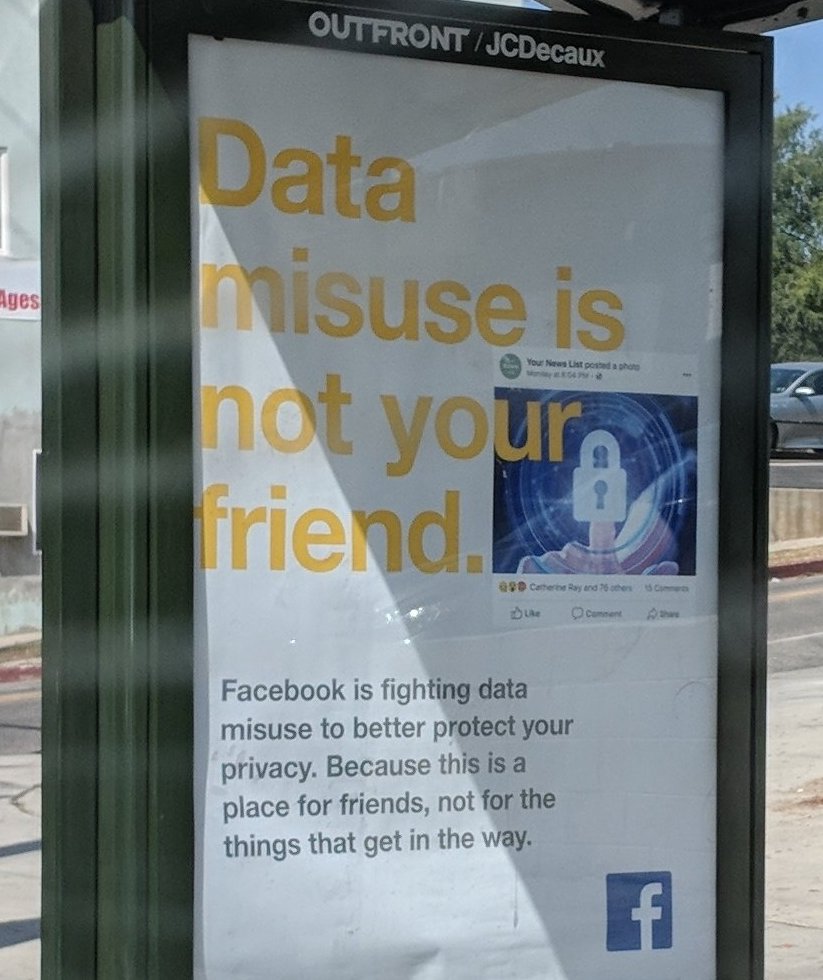

I think therapy refers to where the focus is shifted off the actual focus. For example, is a lack of signups really a UX problem that needs a series of design workshops, or is it that your service sucks and no-one wants to use it? Would Facebook really need to run this ad campaign3 if they actually did care about data misuse?

Despite how obvious these methods can seem, somehow the internal logic of large bureaucratic organisations manages to perpetually convince themselves that this works, that the product is fine and it is it the user that is at fault. Overall, in every community I’ve worked in this has led to ‘consultation fatigue’. Community memory is much, much longer than any funded project, webapp, or commission. People will and do notice if your engagement process, however well designed, has no actual potential to change whatever it is you’re developing.

Tokenism

Most initiatives I see branded as ‘co-production’ fall under what Arnstein describes as ’tokenism’. As a perpetual cynic, I generally categorise tokenist initiatives as ‘market research plus’. In this model, while there might be a thorough consultation process, there would never be any way for people to say “actually we’d rather you let us manage this instead”.

“Informing” is the first rung on this part of the ladder.

“Informing citizens of their rights, responsibilities, and options can be the most important first step toward legitimate citizen participation. However, too frequently the emphasis is placed on a one-way flow of information - from officials to citizens”.

A big problem with this one-way flow is that rarely do people ‘upstream’ bother to find out if people can actually access and understand the information given, whilst internally celebrating a perceived openness and transparency. I think the worst offenders for this are initiatives that usually go under the banner ‘big data’, ‘open data’, ‘citizen science’, and so on. These projects frequently seem to have the unspoken belief that if information is published in an ‘open’4 enough format and represented in a nice enough infographic, somehow things will change by themselves, and that if people can’t understand this stuff that’s their problem. Needless to say, I disagree. Knowledge is not neutral, and if it needs to have an impact then this cannot be done without directly working with the people it’s being created on behalf of.

‘Consultation’ is the next rung. ‘Consultation’ is a word thrown around a lot as a sort of fix-all panacea when there’s an obvious community tension.

“Inviting citizens’ opinions, like informing them, can be a legitimate step toward their full participation. But if consulting them is not combined with other modes of participation, this rung of the ladder is still a sham since it offers no assurance that citizen concerns and ideas will be taken into account.”

This is an improvement on ‘informing’ in many ways. Getting a group of people in a room to have a chat about something in many ways is the only way things can start to change. It is just that though in most cases: a start. The risk is that it can simply be a box-ticking exercise for the consulter, and a tragic waste of time for the consultee. This is the main category of ‘oh crap we messed up’ consultations. Usually large organisations such as property developers or city councils realise that toes have been stepped on, sometimes due to direct action by the residents affected. They then invest in consultations on their terms, with no built-in assurances of what will be done when the consultation is complete. This is an enormous cause of consultation fatigue, especially when it comes shortly after one of the non-particpation methods mentioned above, and even more so when paired with a PR campaign that attempts to convince everyone how good it is that they’re doing a consultation (see: therapy).

The final rung in this category – ‘placation’ – is the natural extension of this, in which “a few hand-picked ‘worthy’ poor [are placed] on boards of Community Action Agencies or on public bodies like the board of education, police commission, or housing authorities”. Again, this is a great start to genuine community co-production. But again, as the effort involved in making co-production happen increases, so does the potential for bigger perceived wastes of time and rifts. In the most extreme examples, dedicated community activists will get invited to join these boards, spend years feeling like they’re banging their head against the wall, and leave with renewed division and animosity, often on ambiguous and hurtful terms. In other words: don’t put people on your board unless you’re really willing to treat them as you would anyone else ‘within’ the existing organisation.

I think the better tech initiatives fall into this category: well meaning, but fundamentally restricted by the kinds of change that the host organisation is willing to make. As mentioned in the introduction you can do all the engagement and research you like, but if that isn’t paired with a change in the way decisions and funding is allocated then it’s usually just well disguised market research with little potential for transformative social change.

Citizen participation

At the top of the ladder is what I believe to be the only way to achieve genuine progressive social change, direct citizen participation with the groups and people you are seeking to help. The three forms of this: ‘partnership’, ‘delegated power’ and ‘citizen control’ to me mostly refer to exactly how far power is delegated: from control over the budgets and project outlines of a few dedicated programs, to total power over entire commissions. Briefly:

- Partnership: “Power is … redistributed through negotiation between citizens and powerholders. They agree to share planning and decision-making responsibilities through such structures as joint policy boards, planning committees and mechanisms for resolving impasses.”

- Delegated power: “Negotiations between citizens and public officials result in citizens achieving dominant decision-making authority over a particular plan or program … Citizens hold the significant cards to assure accountability of the program to them. Powerholders need to start the bargaining process rather than respond to pressure from the other end.”

- Citizen control: “A degree of power (or control) which guarantees that participants can govern a program or an institution, [and] be in full charge of policy and managerial aspects … A neighbourhood corporation with no intermediaries between it and the source of funds is the model most frequently advocated.”

By way of example, PlaceCal came out of a ‘citizen control’ project managed by GFSC’s Prof Stefan White called Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods (MAFN). This project gained funding to spend over four years on making four areas of Manchester more age friendly5. The approach, on paper, was simple: hire the minimum staff needed to develop a partnership, manage the project and produce an evaluation over the four years, and then allocate all the rest to the partnerships (44% or £324,000) to decide what they wanted to spend it on.

This decision ended up framing the entire project. Residents and community groups were trained in participatory budgeting, meeting facilitation and legal structures, asset based community development theory, and involved at every stage in production of research findings. The project conducted over 6,000 conversations with groups and working with residents consolidated them into several Age Friendly Action Plans. One of the major findings from this process was the perception by residents that there’s ’nothing to do in my area’, which led directly to PlaceCal, itself a co-produced and community-led project that’s currently working towards full community ownership.

MAFN itself was based on the C2 Connecting Communities programme, which began in the Beacon Partnership in Cornwall. As a response to coping with an impossibly demanding caseload, neighbourhood health workers introduced a community-led intervention that reversed the decline of a heavily stigmatised estate of 6,000 people. The Beacon project became a national flagship for resident-led community renewal and health improvement. From being a ‘police no-go area’ in 1996 with 50% of children on child protection register, after the first year overall crime down 50%, unemployment down 71%, educational attainment up 100% and child protection down 42%. C2 provide a solid methodology for exploring this kind of intervention on their website.

Working in this way therefore benefits not just individual projects but creates a social and political context for radical new projects that could not be conducted otherwise. Each project builds on the previous one, working with existing efforts, rather than that sinking feeling starting a new group, event or project from scratch, again.

Conclusion

Aiming for full citizen participation is very hard work and will become the whole project and not an add-on to do further down the road. A genuinely co-produced project will fundamentally change the nature of the work conducted, changing the emphasis from a focus on developing solutions, whether technological or otherwise, to one on creating a creative partnership around a shared purpose. Key to this is engaging directly in the actual barriers faced by residents on a day-to-day basis. When working in this way, technology will no longer be centre stage in the project, instead becoming one of many tools that can be used to help people work together.

Of course, this approach isn’t always relevant. If your primary purpose is commercial, or your objectives don’t involve citizen participation, then another approach is needed. However if, like us, you are attempting to create interventions on behalf of the most isolated and vulnerable in society, we think there is no other way of getting things done.

Got any comments or suggestions? Let us know on Twitter @gfscstudio.

-

‘Tech’ has many meanings, I use it here to refer to ‘high tech’ businesses and social enterprises that focus on creating apps and websites, and the culture that these organisations create. I will write more on this in future and would welcome helpful disambiguations! ↩︎

-

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of planners, 35(4), 216-224. ↩︎

-

Image from Justin Li on Twitter ↩︎

-

The ‘open’ in this context usually referring to publicly published open source, with other forms of ‘openness’ implied as an ‘obvious’ follow-on. ↩︎

-

Hulme and Moss Side (one area), Moston, Burnage, and Miles Platting. ↩︎